C’mon now, admit it. You’ve been faced with it too: Not knowing what print sizes your file will fit on without cropping.

C’mon now, admit it. You’ve been faced with it too: Not knowing what print sizes your file will fit on without cropping.

The answer is all in the colon. No, not THAT one, this one ==> : These two quiet dots carry the full weight of the answer to the problem and it comes in the form of proportions.

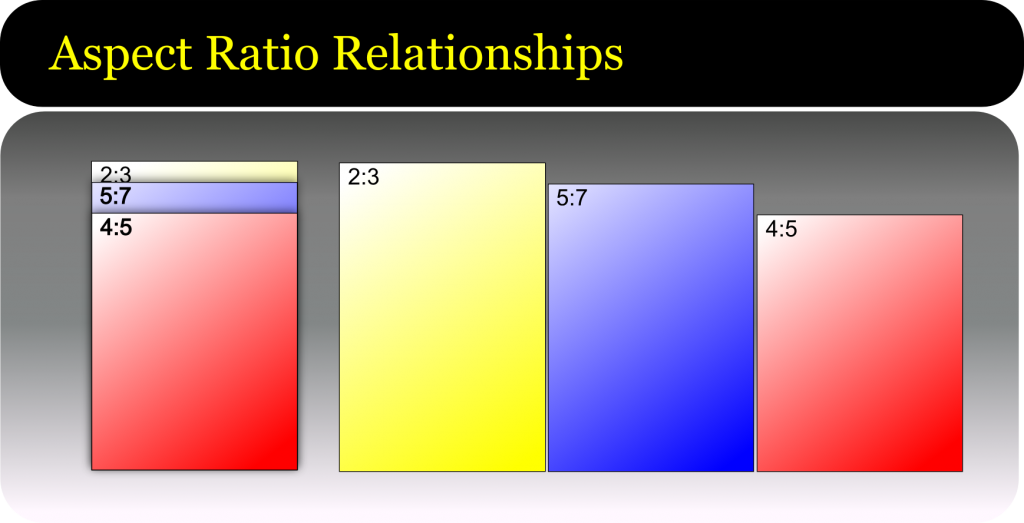

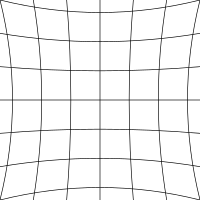

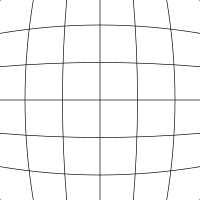

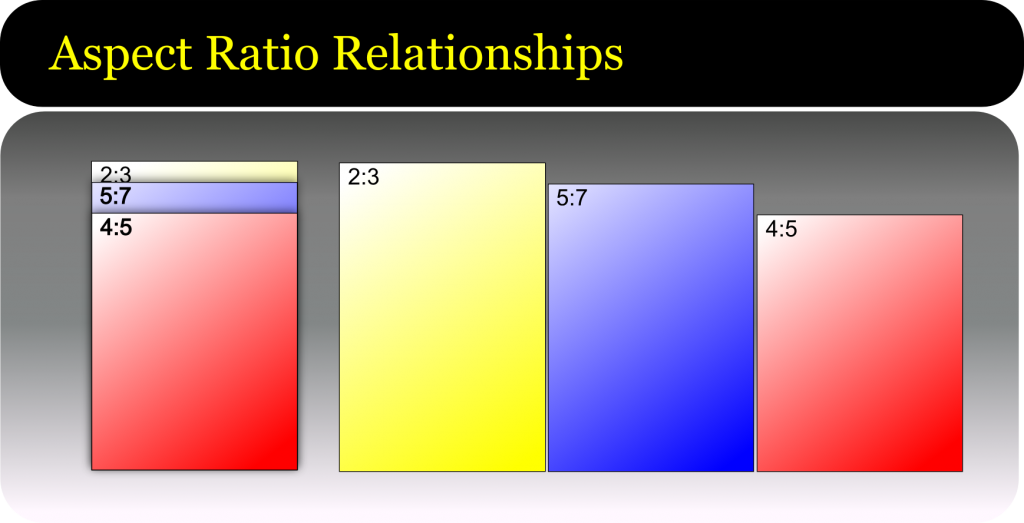

Proportions, or “aspect ratios” are really just the comparison of one dimension to the other , ie. how height compares to width. When the proportions of your image, match the size you want to print, we say that it “pros out”. If it does not match we call this “fails to pro”. Pro, of course. being short-hand speak for “proportions.”

Proportions are used for many purposes in the graphic and photographic arenas, sometimes for technical reasons i.e. to fit a print size, sometimes for aesthetics – each ratio has its own gestalt – or feeling.

Images have their aspect ratios determined by either the camera or the cropping. For the purpose of our discussion, we are determining ratios to know if we will need to crop our image more to get it to fill all of a given print size. Cropping is required if the image aspect ratio does not match the print size aspect ratio.

Proportions are written as two numbers separated by a colon, such as 1:3 – meaning that for every 1 the other gets 3. So a print that is 1 inch on the shortest side would be 3 inches on the other side. Or an images that is 4 inches on the shortest side would be 12 on the other.

Note: officially when you verbally state a ratio, that little colon would be substituted with the word “to”, as in a ratio of 1 to 3. Now say this out loud: “1 to 3”. Sounds like you just counted to three right? Welcome to english where we have two too many toos to go around. Since a great deal of our customers are from around the globe, and we don’t want to risk confusion in a print order, we prefer to use the word “by” instead. As in “a 4 by 5 aspect ratio”.

The Basics

The aspect ratio is determined by reducing dimensionA:dimensionB to the lowest common denominator. Most print sizes will divide by 2 or 3 A few simple examples are a 4″x6″ print and an 8×10″ print.

Finding the ratio of the 4×6 would look something like this:

4×6 = 4:6 and the smallest number that these numbers can be divided by is 2.

4/2 = 2 : 6/2 = 3 No other whole number division can occur, so our aspect ratio is 2:3 or “2 by 3”

The 8×10 would go something like this:

8 x 10 = 8:10

Neither number divides by three down to a whole number, but we can divide equally by two.

8/2 = 4 : 10/2 = 5 No other whole number division can occur, so our aspect ratio is 4:5 or “4 by 5″

Let’s add another example: the 16×24 print size.

the 24″ dimension divides equally by three (3×8) but the 16” dimension does not (16/3= 5.33333) so we’ll try dividing by 2:

16 / 2 = 8 : 24 /2 = 12 and we get 8:12. We can take this further, yes?

8 / 2 = 4 : 12 / 2 = 6 and now we have 4:6 and we can still go down further.

4/2 = 2 : 6/2 = 3 No other whole number division can occur, so our aspect ratio is 2:3 or “2 by 3″

Now you might recognize that last one as the same ratio we determined from the 4″x6″ print. So our 4×6 and our 16×24 all have the same 2:3 aspect ratio. This means that an image that fits our ratio will scale to either size print without the need to crop off image area.

Some print and image sizes might need to multiply up to get to a good whole number. Let’s take a 2.5″ x 3.5” print – commonly called “yearbook wallet size”. These dimensions will not divide by the same amount to reach a whole number, so we must go up. Again, I’ll use the 2 or 3 rule first.

The number two looks like a good fit here:

2.5 x 2 = 5 : 3.5 x 2 = 7 for an aspect ratio of 5:7. These numbers won’t divide down further so we have our final aspect ratio.

Now that we have an aspect ratio, let’s look at what print sizes this will match without cropping:

5:7

x2 = 10″x14″

x3 = 15″x21″

x4 = 20″x28″

x5 = 25″x35″

etc.

These are not very recognizable sizes today, in part because this aspect ratio has not been used in cameras for several generations. The 5×7 print size still exists, but it does need some cropping for most modern images.

So let’s try this with our other sample aspect ratios:

2:3 is the ratio of 35mm, most DSLRs and digital hand-held cameras in the consumer market. Since it’s likely one that most of our readers will have had some experience in, let’s start there.

2:3

x1 = Standard wallet – 2″x3″

x2 = 4″x6″ – Your basic minilab/drugstore print

x4 = 8″x12″ – A common portrait print size. Note that an 8×10 would need cropping

x8 = 16″x24″

x10 = 20″x30″

x12 = 24″x36″

etc.

In this next example you’ll see some very familiar sizes.

4:5

x2 = 8″x10″ The single most popular enlargement size in the USA.

x4 = 16″x20″

x6 = 24″x30″

x8 = 32″x40″

etc.

Let’s answer a common question:

How do I know how much of my DSLR file will need cropping to fit a 16×20 print?

This is pretty straight forward. Let’s start with the short dimension.

So we have a 16X20 print and a file with a 2:3 aspect ratio.

Divide the short side of the print by the larger of the ratios: 16/ 2 = 8

Take the result and multiply by the longer: 3 x 8 = 24.

Result of 24 minus the print size of 20 and the remainder is 4

So this process shows us that if we enlarge the file to fit the short side to the 16″ dimension, we will have an extra 4″ of image area that will get cropped from the long dimension.

If the last step of the equation leaves you with a number that is smaller than the print size, then you need to begin again, this time starting with the longer print dimension.

Whew! Still have questions? Ask them in the comments below and I’ll do my very best to answer them.